This is a blog post about the paper Computational ad hominem detection presented at ACL2019. In this post, you'll learn the following things:

- What ad hominem attacks are, although if you're reading this blog post, you'll probably already know about this.

- What's challenging about detecting those attacks.

- How we tackled this problem by merging multiple natural language processing (NLP) technologies.

- The limitations of our model, along with some pointers for future work.

The ad hominem attack

Ad hominem literally means "to the person", and the term is used when an argument directs to the person instead of assessing the argument itself. There are multiple types of attacks, some examples are:

| Example | Type | Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| You're an idiot. | Name calling | 🙂 |

| You were removed from the council for dishonesty, so your philosophy is untrustworthy. | Abusive attack | 🧐 |

| Why are you saying I shouldn't smoke? You have always smoked yourself! | Circumstantial attack | 😱 |

Now, detecting simple name calling seems quite simple with just a keyword based heuristic. Abusive attacks are already a bit more complex, since they attack the character, instead of the argument. However, they still contain negative words, which makes them a bit easier than the circumstantial attack. In this case, circumstances are drawn into the argument, which can be quite broad. For a more detailed discussion, see Walton (1998).

The data

The datasets are sourced from UKPLab/argotario and UKPLab/naacl2018-before-name-calling-habernal-et-al. This last dataset contains the bulk of all training data. This data set is in essence a database dump of a Reddit community called Change My View, which focuses on online debating. In this context, ad hominem attacks are unwelcome and thus removed by moderators. The data set contains these labels among other thing and in total, almost 30k reactions are in the dataset, with ~10% ad hominems. Some examples:

What makes corporations different in this case? They have interests too. --- A random redditor, not an ad hominem

In this example, the user asks a question and gives a---rather short---reason. The following example is a bit longer, but starts of nicely by mentioning his/her smugness. At the end, the author attacks the contributions of the other person and thinks those are ad hominem attacks, what a coincidence!

"I'm sorry if your smugness gets in the way. Like I said elsewhere in this thread. Somolia is not close to anything I advocate for so why on earth would I move there? Any time the Somolia "argument" is brought up, I instantly know I'm dealing with someone who refuses to learn the difference between a voluntary society and a third world country ravaged by warlords and foreign policies of other countries. If you want a thoughtful response to an argument, make sure you're not comparing Antarctica to the Bahamas. Otherwise, take your circlejerk, "arguments" elsewhere. You have contributed absolutely nothing to this thread but ad hominem Attacks and the typical liberal/conservative talking points and almost everyone in here knows it." --- Another random redditor, an ad hominem

Model architectures

We created a set of baseline models based on TF-IDF features and word embeddings, as well as some more advanced models. The best performing model is explained in more detail.

Baseline models

Several baseline models are considered, in increasing complexity for the feature inputs and with both neural networks and SVMs. In short, the following models are compared:

- SVM A: our first model is based on a TF- IDF vectorizer and an SVM classifier. The TF-IDF vectorizer uses the top 3000 words from the test set. The SVM classifier is a linear SVM.

- SVM B: this model also uses a linear clas- sifier, but the features are based on word representations. Instead of the TF-IDF vec- tors for a paragraph, the 300 most occurring words from the training set are used. For each of these 300 words, the TF-IDF value is replaced by a weighted word embedding. So for words that don’t occur in a sentence or paragraph, all elements of this vector are zero. Otherwise the word representation is scaled by the TF-IDF value of that word.

- NN: the NN approach continues with the above described vectorizing and uses a neu- ral network for classification instead of an SVM. The output is formed by two sigmoid- activated neurons after one fully connected layer.

Best performing model

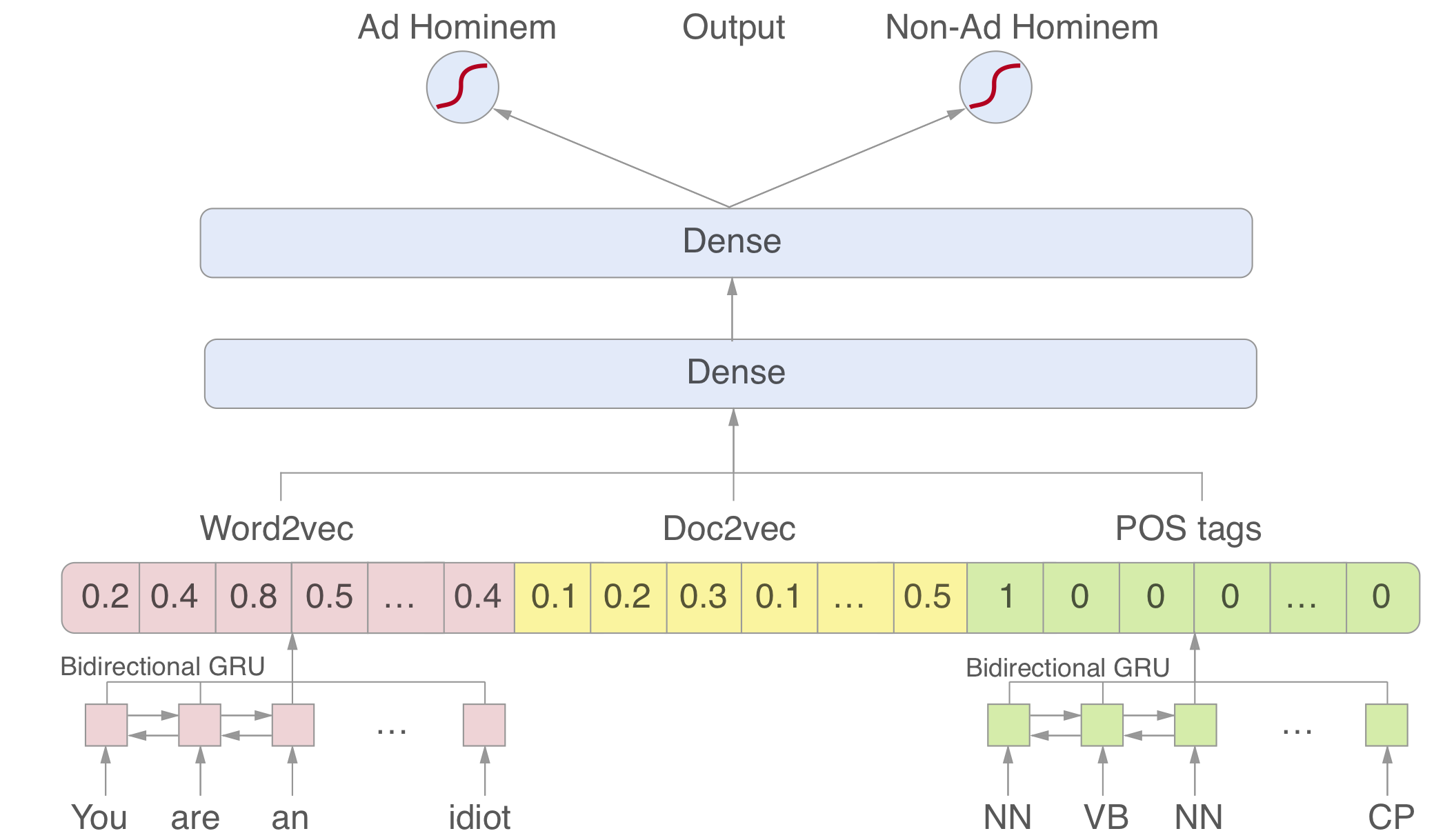

During the project, several classifiers and network architectures were reviewed. The results are incorporated in the paper. The final, best performing network is a bidirectional GRU neural network, with the following features:

Pre-trained word embeddings (word2vec) with a word limit $L$, that can also be tuned as a hyperparameter to the network.

Document embeddings

Part-of-speech tags (NLTK)

These features are combined into a classification network, resulting in a labeling as ad hominem or no ad hominem. For the architecture, we used a fairly standard bidirectional GRU layer for both the POS tags and the word embeddings. The outputs of those vectors are merged with the document vector. This vector can be though of as the difference between what all word embeddings represent individually and the actual document. With the introduction of contextualized word embeddings (i.e. BERT), this could be discarded in future work.

Results

All models were tested on 8018 unseen paragraphs and the results were evaluated with regard to the accuracy $ACC$, recall $R$, Gini coefficient $GI$, and the F1 score. The following table describes the results. As an external baseline, the baseline by Habernal et al. (2018).

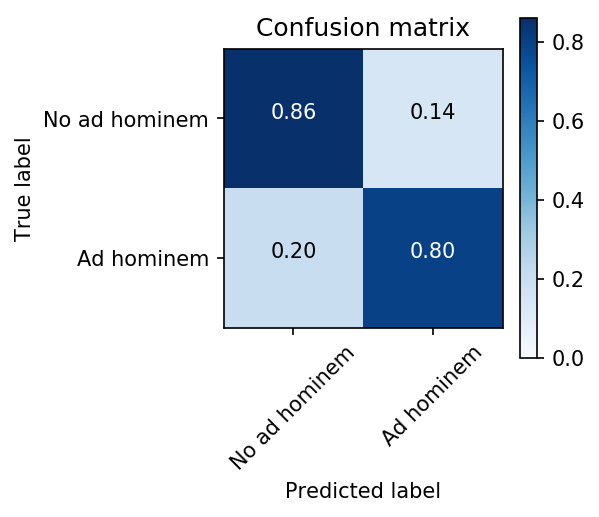

For the best performing model---with regard to the recall, Gini coefficient and F1 score---the confusion matrix is as shown below. Since the dataset is not balanced, the accuracy in itself is not a trustworthy metric for classification performance.

Limitations and future work

There are some obvious steps to improve the results we just presented, like collecting more data or using contextualized word embeddings. However, in the work we presented, we also noticed several interesting limitations, of which two are listed here.

Positional effects

One issue with RNNs is that not all positions are considered equally, meaning the impact of attacks at the beginning or the end of a paragraph are higher than those in the middle. A simple way to mitigate this would be to considered each sentence in isolation. However, there are attacks that span multiple sentences, so we don't consider this solution ideal. A better course of action would be to incorporate attention, or even move to a seq2seq model with better interpretability as a bonus.

| Paragraph | Probability |

|---|---|

| Augmented recurrent neural networks, and the underlying technique of attention, are incredibly exciting. You’re so wrong and a f*cking idiot! We look forward to seeing whathappens next. | 0.39 |

| You’re so wrong and a f*cking idiot! Augmented recurrent neural networks, and the underlying technique of attention, are incredibly exciting. We look forward to seeing whathappens next. | 0.79 |

Catastrophic forgetting

Since we also presented an online demo with online learning to source more data, we think it's relevant to highlight the issue of catastrophic forgetting, which is well-know in the context of transfer learning. By retraining a network on the added data, it will forget the previously trained weights. This then results in a drop in performance, like accuracy.

Selected citations

Ivan Habernal et al., “Before Name-Calling: Dynamics and Triggers of Ad Hominem Fallacies in Web Argumentation,” in Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers) (Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers), New Orleans, Louisiana: Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018), 386–96, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N18-1036.

Douglas Walton, Ad Hominem Arguments (Studies in Rhetoric & Communication) (Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1998).

Christoph Hube and Besnik Fetahu, “Neural Based Statement Classification for Biased Language,” CoRR abs/1811.05740 (2018), http://arxiv.org/abs/1811.05740.